Dear Clearwater,

I first met Pete Seeger in 1968, when he told me that he was raising money to build a replica of a cargo sloop that had plied the river a century ago. The sloop was called Clearwater, and it was run by the Hudson River Sloop Restoration (now Hudson River Sloop Clearwater, Inc.), which Pete said was probably the first organization to have a bard as chairman of its board.

I first met Pete Seeger in 1968, when he told me that he was raising money to build a replica of a cargo sloop that had plied the river a century ago. The sloop was called Clearwater, and it was run by the Hudson River Sloop Restoration (now Hudson River Sloop Clearwater, Inc.), which Pete said was probably the first organization to have a bard as chairman of its board.

Launched the following year in Maine, Clearwater was on its way to New York City. Seeger, his fellow musicians, and lots of volunteers planned to sail her from port to port, teaching people to love their river. This was my opportunity to see Pete again, and maybe get a chance to sail on the sloop. My mind pondered these uncertainties, but my heart knew where it wanted to be.

So I headed for New York, where hundreds of people lined South Street Seaport in a spectacular expression of support. Under a skyline draped in gray, a fleet of tugs, sail boats, and other launches surrounded the broad-beamed, green-hulled sloop. A single mast held its billowing white canvas aloft, while young activists and musicians–now newly minted seafarers–stood proudly upon its deck.

The sloop glided into its berth and within moments Pete Seeger–bearded and wearing a sailor’s cap–stepped up on the stage and surged forward in the breeze to share his vision.

The sloop glided into its berth and within moments Pete Seeger–bearded and wearing a sailor’s cap–stepped up on the stage and surged forward in the breeze to share his vision.

“Who’s going to clean up this river of ours? No polluter, no politician, is going to lift a finger unless we insist on it. So, we have to make ourselves heard! We’re all in this environmental thing together. Not even a millionaire can escape it. We’ve got to take action right now. We may have to start small, but each of us can do something.”

It was evident not only in what he had written around the edge of his banjo—“This machine surrounds hate and forces it to surrender”—that Pete embodied love in all that he did.

“The idea is simple,” he continued that day. “We want people to come down to the river again. But the most important thing is to get together. All of us–young and old, black and white, rich and poor, long hair and crew cut–because we just won’t make it unless we can talk to one another and agree on what we have to do.”

So I joined Clearwater’s maiden voyage up the Hudson River as the newest crew member, and the only non-singing one, the others were friends of Pete and musicians in their own right—‘Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Gordon Bok, Brother Fred Kirkpatrick, Jimmy Collier, Len Chandler, Don McLean, Lou Killen, Andy Wallace, Jon Eberhart, and Captain Allan Aunapu.

So I joined Clearwater’s maiden voyage up the Hudson River as the newest crew member, and the only non-singing one, the others were friends of Pete and musicians in their own right—‘Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Gordon Bok, Brother Fred Kirkpatrick, Jimmy Collier, Len Chandler, Don McLean, Lou Killen, Andy Wallace, Jon Eberhart, and Captain Allan Aunapu.

Departing the seaport, we passed the Statue of Liberty, sailing around the tip of Manhattan, while skyscrapers and factories loomed overpoweringly from the shoreline. I thought of the travelers who had made this same voyage to Albany in the days when sloops once carried cargo and the Indigenous people who traversed the watershed for thousands of years before them. I laid back, taking everything in. I knew this was where I belonged.

50 some years later, after much more reflection on this and the series of adventures that followed, I am deeply grateful to Pete Seeger for this opportunity that dramatically altered the direction of the rest of my life. His awareness then that all things are tied together, that when you start to clean up the river, you have to clean up society too, has formed the framework for everything I have done since, in working for the betterment of the whole. Clearwater, its mission, message, the community and the movement it has built over more than 50 years, is still what the world needs most right now. As Pete used to say, “Keep on keepin’ on!

Robert Atkinson

Excerpt from, Year of Living Deeply: A Memoir of 1969, by Robert Atkinson, adapted by Clearwater for brevity and continuity as a part of the Generations Story Archive series.

Excerpt from

Year of Living Deeply: A Memoir of 1969

by Robert Atkinson

… One morning, a local newspaper headline caught my eye: “Hudson River Sloop Arrives at Port Jeff Today.”

I immediately remembered the year before when I had first met Pete Seeger, a friend of Harry Siemsen, the Catskill Mountain folk singer I had interviewed. Pete had given me some background information about Harry, and he also told me that he was raising money to build a replica of an old cargo sloop that had plied the river a century ago.

He and lots of other volunteers would sail her from port to port, teaching people to love their river again. The sloop was called the Clearwater, and it was run by the Hudson River Sloop Restoration, which Pete said was probably the first organization to have a bard as chairman of its board.

Recently launched in Maine, the Clearwater was on its way to New York City. This was my opportunity to see Pete again, and maybe sail on the sloop. But would he remember me? Would there be room for me? What would I do onboard?

While my mind pondered these uncertainties, my heart knew where it wanted to be. So, I headed for Port Jeff. Letting my courageous self take over, I found the sloop at the dock and spoke to Pete.

“Do you remember last year, when we talked about your project, and you said I might be able to help? I really would like to. Maybe I could gather stories from people who can tell us what the river was like in the days of the sloops.” “I think you’ve got something there,” the troubadour replied. “The history of the river should be told, too. We could use your help on that. Can you meet us in New York this

weekend and sail with us so we can work out the plans?” “I’d love to!”

I could hardly believe my ears. For three years Pete and his singing friends had given “sloop concerts” up and down the Hudson, raising money to build the Clearwater and save the river. His dream had come true, and now I was to have a part in it.

The next day, hundreds of people lined New York’s South Street Seaport pier in a spectacular expression of support. Under a skyline draped in gray, a fleet of tugs, sail boats, and other launches surrounded the broad-beamed, green-hulled sloop. A single mast held its billowing white canvas aloft, and young seafarers stood proudly upon its deck.

The sloop glided into its berth, as the crowd remained expectantly silent. Within moments Pete Seeger—the banjo-playing, mind-stretching, shelter- giving humanitarian—bearded and wearing a sailor’s cap, stepped up on the stage and surged forward in the breeze to share his vision.

“Who’s going to clean up this river of ours? No polluter, no politician, is going to lift a finger unless we insist on it. So, we have to make ourselves heard. We’re all in this environmental thing together. Not even a millionaire can escape it. We’ve got to take action right now. We may have to start small, but each of us can do something. First, we can all do some reading. Get copies of the books we have here on the ship. Find out the facts about the environmental crisis. Then talk it up.”

“The idea is simple,” he continued. “We want people to come down to the river again. But the most important thing is to get together. Because we just won’t make it unless we can talk to one another and agree on what we have to do. All of us. Young and old, black and white, rich and poor,

longhair and crew cut. We hope people will say, ‘Gee, this river is a mess. Ought to do something about it.’ You see, everything in the world is tied together. You clean up a river, and soon you have to work on cleaning up society. Let’s all get together and make this thing work. We can do it. Don’t let anyone tell you we can’t. But we have to want to do it!”

As he broke into song, “Sailing down my dirty stream, still I love it and I’ll keep my dream,” I couldn’t help but think along with him “that some day, though maybe not this year, the river will once again run clear.”

When the music stopped, the people cheered, echoing his enthusiasm. Then the haze that had blurred the skyline slipped silently away.

I knew this was where I belonged. It was evident not only in what he had written around the edge of his banjo skin—“This machine surrounds hate and forces it to surrender”—but in how he embodied love in all that he did.

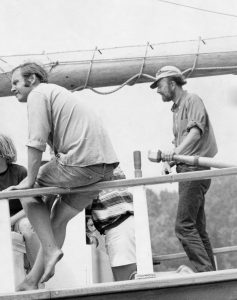

Later that afternoon, I joined the other seafarers for the sloop’s maiden voyage up the Hudson River. I was the newest crew member, and the only non-singing one. The others—“Ramblin’” Jack Elliott, Don McLean, Gordon Bok, Brother Fred Kirkpatrick, Jimmy Collier, Len Chandler, Lou Killen, Andy Wallace, Jon Eberhart, and Captain Alan Aunapu—had all performed on stage with Pete.

We sailed around the tip of Manhattan, passing the Statue of Liberty and entering the mouth of the river in a boat the people of the Hudson Valley hadn’t seen in nearly a hundred years. I laid back, taking everything in.

That first day, skyscrapers and factories loomed overpoweringly from the shoreline. Clouds of smog hung over our heads. Conveyor-belt highways were teeming with cars, driven by people who were themselves driven by the demands of time and place.

Our sloop meandered along at a pace set by winds and tides. It took most of the day to reach the George Washington Bridge, at the north end of the bustling island. I thought of the travelers who had made this same voyage to Albany in the days when sloops carried real cargo as well as passengers. They must have seen lush grass and wildflowers growing along the shore, and taken in the sweet smells coming from them.

That night, at anchor in a quiet cove, after a delicious dinner from the Clearwater galley, most of us followed Allan, Jack, Lou, and Jimmy into the small hold below the foredeck. There they sat around picking and singing whatever tunes came into their heads. Allan sang some Caribbean songs he had learned while sailing there; Jack let loose with some Woody Guthrie songs he had picked up while traveling with him. For hours we listened to songs, old and new, never wanting the music to stop. And I found that sing- ing is not only a way of earning a living but more importantly a way of life.

The next day, the rock wall of the Palisades, topped with hemlocks, oaks, and tulip tress, towered over our little sloop like a natural fortress, as we plied our course, drifting lazily along.

I began to wonder how I would fit into the routine of shipboard life, feeling out of place among seasoned seafarers, a stranger upon unfamiliar waters, with all knowing their tasks and roles.

I asked Allan, our captain, who was as much a virtuoso on the ship’s halyards as on his guitar strings, “How can I play an equal part in this community?”

Peering over the side of the ship, with his golden locks flowing in the wind, he replied, “Listen to the music of the surrounding waters. The fish silently reveal a secret. They swim as one, sensing the spirit that binds them with their surroundings. With trust and a common will, they carry on as an endless wave in the sea of creation.”

At that moment, in the Tappan Zee, the river valley came alive with the call of adventure.

Our every move was determined by a wind charged with power. We took a tack to starboard, and with a mighty slap, back came the mainsail, flap- ping loosely across the deck. A gust filled the canvas, and as we picked up our course on the port, the lines were pulled taut. Listing in a brisk gale, we headed for a cove, seeking safety as the ship’s rail dipped below the sea spray.

At the foot of stern mountains, unseen streams roared down into the river. Amid the sea’s ever-breathing energy I, the novice, began to feel more comfortable. I pitched in, hauling a line, and found my place within the seagoing community.

After the squall passed, I climbed out onto the bowsprit and rested in its hammock-like netting. There I regained a perspective on the sea’s inner order.

Ahead lay Nyack, our first port of call, where we docked for a sloop festival. By sunset a few visitors were still aboard the sloop. Some were talking with crew members on deck, while others were singing by the tiller as Allan played his guitar.

Sitting on the quarterdeck was a young lady in a wide-brim hat, gazing out over the river. She beckoned me with her soft, silent presence. But without knowing just what I would say, I walked over and greeted her, “Hi. Are you from around here?”

She looked up and smiled. We spoke for a few minutes. I learned her name was Judy and that she was home from college for the summer. We decided to leave the sloop for a walk in the park.

We soon came to a playground and jumped on the swings. After a while, we tried the seesaw, learning little bits about each other with every up-and- down movement of the plank. We walked up a hill, rolled down it, and lay in the warm grass, talking some more.

Later, as we headed back to the sloop, I said, “Hey, you know, this has been a real special night.”

“Yeah, it has.”

“I sail again tomorrow. We’ll be in Albany by next weekend.” “That’s the day of the festival,” she said excitedly.

“That’s right. We’ll be doing another sloop festival there, too.” “No, I mean Woodstock!”

“Oh, that one. Are you going?” “Yeah.”

“Well, maybe we could meet there.”

“They’re expecting thousands of people,” she exclaimed. “How would we ever find each other?”

“Easy. We’ll meet in front of the stage at noon on Sunday.”

“Well, I guess we could try it.”

“Great,” I said. “Don’t forget.”

“I won’t. Well, I’ve got to find my little sister and get her home.” “It’s been really nice. See you Sunday.”

“Yeah. See you at Woodstock.”